28 years

of

Community Service

of

Community Service

MUNTING NAYON

News Magazine

Operated by couple Eddie Flores and Orquidia Valenzuela

News and Views of the

Filipino Community Worldwide

Filipino Community Worldwide

Struggles for Democracy in the Philippines

by Renato Perdon (Bayanihan News)

Sydney, Australia

May 27, 2015

... in the short space of eight months our Government has passed through three stages; in the beginning it had a Dictatorial form, then it was called Revolutionary, and now it is a Republic, which means that we have used every effort to clothe it in the most splendid garments in order that all nations may see that we also follow their footsteps by giving the citizens a just and pacific government — Aguinaldo

For more than three centuries the Filipinos were ignorant of the idea of ‘state’ and lived without any notion of national solidarity. This political situation was true despite European intrusion into the Filipino way of life, Jose Rizal, the foremost Filipino reformist, observed in 1891 that ‘there is ... in the Philippines a progress of improvement which is individual, but there is no national progress’.

This could be the reason why, in spite of countless revolts and uprisings against the long tyrannical Spanish rule, no effort had emerged, on the part of the Filipinos, to bring these struggles into a cohesive national action. It was only the Philippine Revolution of 1896 that paved the way for the formation of an idea of a Filipino state. At long last, Filipinos realised that they had something in common, a common grievance against the Spaniards.

The 19th century saw a change in attitude among Filipinos and social consciousness developed. the opening of the islands to international trade in 1834, the inauguration of the Suez Canal in 1869, followed by the penetration of European liberalism into the Filipino frame of mind, and the emergence of the middle class who brought to the Philippines the revolutionary ideas – the philosophical basis of the French and American revolutions – opened the gates to new concepts of authority, responsibility and rights. The isolation of the Philippines from the outside world came to an end. The ordinary Filipino no longer talked of his bayan, referring to his village or town, his birth and childhood. He started to think of his bayan as the whole Filipino nation in which he had an important part to play. This was the Philippine state — his motherland.

In August 1896, the Filipinos took arms against the Spaniards, however, that the odds were against them. A peace agreement between the Filipinos and the Spaniards, known as the Pact of Biyak-na-Bato, signed in December 1897, ended the first phase of the revolution. It was the only salvation. It gave the Filipino revolutionary leaders a convenient way out of an untenable position. The pact was signed and the war ended, at least, temporarily. General Emilio Aguinaldo and his officers went to Hong Kong in voluntary exile. The agreement, signed by both parties in bad faith, however, was bound to fail. Indeed, it was ignored and failed.

There was plan on the part of the Spaniards to comply with the stipulation of the Pact of Biyak-na-Bato. In the other camp, the Filipino leaders were of the same frame of mind. They were already thinking of renewing the fight even before their departure for Hong Kong in December 1897.

Upon his return to the Philippines in May 1898 General Aguinaldo regrouped his revolutionary forces and vigorously pursued the plan against the Spaniards. The ultimate goal was to form a Filipino government. Initially, a federal type of government for the Philippines was studied, but the prevailing condition required a government organisation with a strong executive arm. On 24 May 1898, he established a dictatorial government administered through decrees.

General Aguinaldo revoked all orders issued by the Biyak-na-Bato Government prior to the signing of the 1897 peace agreement and all commissions issued to officials of the revolutionary army, provinces, and towns were annulled. The population was urged to observe humanely the laws of war in order to show the world that Filipinos were ‘sufficiently civilised and capable of governing themselves’. A corresponding penalty was prescribed, including death for crimes of murder, robbery and rape.

Events developed quickly. On 12 June 1898, General Aguinaldo declared Philippine Independence from Spanish control. The Philippine national flag and anthem, symbols of Filipino nationhood, were officially unfurled and displayed to a jubilant crowd. The Dictatorial Government lasted until 23 June 1898 when a Revolutionary Government was established.

The common belief of the leadership was that the country with its natural resources and energy sufficient to free itself from the ruin and abasement brought about by Spanish colonisation, the country can claim a modest, though worthy, place in the concert of free nations. These ideals became the basis of the revolutionary government with a simple governmental structure consisting of a president and four departments. A Revolutionary Congress existed composed of provincial representatives. Instead of a judiciary, a permanent commission heard suits from provincial governments and for military justice. Before the end of September 1898, key officials in the Filipino government, including military officers, were appointed.

This first Philippine Republic, the first democratic republic in Asia, was proclaimed on 21 January 1899. Unfortunately, it was a short-lived government that only survived two years and two months, destroyed by force of American arms. It was the embodiment of Filipino aspirations to control their destiny and to have a say in their own affairs. In spite of being branded by the Americans as an ‘ephemeral republic’ or ‘the paper government of the Filipinos’, and dismissed as a mere ‘lesson in patriotism’, the First Philippine Republic, also known as the Malolos Republic, was a working government with notable leadership headed by President Emilio Aguinaldo and assisted by military officers and a civilian cabinet. State laws on education, public administration, agriculture, health, trade and industry, commerce, postal and telegraphic communication, government fiscal system, local government, judiciary, elections, pensions for war veterans and their widows and children and others were implemented. The government was supported by incomes raised from taxes, licence fees, voluntary contributions or war taxes.

As a fledgling nation, the Philippine Republic had to make its ideals and aspirations known to the world so that foreign powers would respect and recognise its independence. Between 1896 and 1901, hardly five years, constitutional projects, program of reforms, organic decrees, manifestos, memorials, handbills, declarations of rights, and other documents were issued to define the national political ideals. El Heraldo de la Revolución (The Herald of the Revolution), the official organ of the government founded on 29 September 1898.

Privately-owned newspapers took up the Filipino cause. Most famous of these periodicals was La Independencia (The Independence), edited and partly owned by General Antonio Luna. A number of Filipinos also published materials supporting the government like the La República Filipina (The Philippine Republic), La Libertad (Liberty), Ang Kaibigan nang Bayan (People’s Friends), Columnas Volantes (Fly Sheets), La Federación (Federation), La Revolución (The Revolution), and many more, including local newspapers and publications.

During its brief life, between 1898 and 1901, the First Philippine Republic had all the attributes of a State. The people rallied behind its cause; a revolutionary and later a republican form of government controlled a vast territory, not only in the main island of Luzon but in the Visayas and Mindanao areas. Philippine independence was declared on 12 June 1898. What it failed to accomplish was its recognition by foreign countries and the rest of the world.

A significant feature of the Revolutionary Government was the creation of the Department of Foreign Relations, Navy and Commerce with a Bureau of Foreign Relations responsible for diplomatic activities, including diplomatic dispatches and correspondence from the Philippine Republic to foreign governments. A Revolutionary Committee abroad was organised to negotiate with foreign ministries concerning the recognition of Philippine belligerency and independence.

The inclusion of foreign recognition in the overall revolutionary strategy indicated the Aguinaldo government’s awareness of the implication of the declaration of Filipino independence. At this stage, under international law, the young government had already achieved, the first in Asia, all the requisites of an organised independent state, for example, people, territory, and government, not to mention a national flag and anthem. Even so, recognition of its existence as an independent state by foreign powers was not in sight. In the meantime, the Filipino government existed as de facto government, devoid of official links with the outside world.

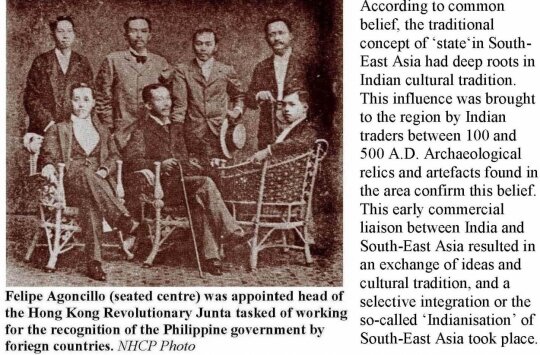

In August 1898 the Filipino government published in Hong Kong papers the text of the Filipino independence proclamation and a manifesto addressed to foreign governments. The manifesto explained the true cause of the Philippine Revolution and appealed to various foreign governments to recognise Filipino belligerency and independence. General Aguinaldo converted a group as the Hong Kong Revolutionary Committee, composed of a central directorate, members and foreign correspondents or diplomatic agents assigned in France, Great Britain, the US, Japan and Australia. The ‘diplomatic agents’ named were Pedro Roxas and Juan Luna for France; Antonio Maria Regidor and Sixto Lopez for Great Britain; Felipe Agoncillo for the United States; Mariano Ponce and Faustino Lichauco for Japan; and Heriverto Zarcal for Australia.

All efforts however to gain foreign recognition of the Philippine Republic failed. No favourable response was accorded the de facto Filipino government by the leading European powers such as Great Britain, France, Russia, Germany and Japan, the only Asian power of the time. The reluctance of the foreign powers to commit themselves to either side of the conflict was a decision that preoccupied diplomatic representatives of various countries in the United States, particularly those coming from Europe. During the early stage of the Spanish–American War, Europe was planning to act in concert to rebuff the United States for its decision on the Cuban issue that resulted to the war, however, the American victory at the Battle of Manila Bay on 1 May 1898 changed the course of Philippine history.

The transition from a revolutionary government to a democratic republican form of government was established through a constituent body that framed the organic law of a Philippine state. Late in 1898, the Philippine Revolutionary Congress, also known as Malolos Congress, was inaugurated in the town of Malolos, Province of Bulacan, north of Manila, to frame the constitution of the First Philippine Republic. By this time, the Filipino Revolution instigated by the masses in 1896 had been taken over by the leadership of the ilustrados, sons of Filipino middle class families. The Malolos Congress drafted a Constitution considered by many as the ‘most glorious achievement of the noble aspirations of the Philippine Revolution’. It was a conclusive proof, before the civilised world, of the culture and capacity of the Filipino people to govern their own affairs.

The Constitution established a free and independent Republic of the Philippines and provided for a ‘popular, representative, alternative and responsible’ government based on the principle of separation of powers — executive, legislative and judiciary. Freedom of religion and the separation of church and state were recognised. The rights of citizens and aliens were safeguarded by a Bill of Rights. An elected Assembly of Representatives exercised the legislative powers while a President elected by the Assembly, performed the executive function of the government. Judicial power rested in the Supreme Court of Justice and other courts created by law. A Chief Justice appointed by the Assembly and concurred in by the President headed the judiciary.

The permanent legislative committee acted as legislative body when the Assembly was not in session. Parliamentary immunity; a penal responsibility of high ranking officials for crimes committed against the safety of the State; a Council of State composed of the President and his cabinet secretaries; and a local government and departmental autonomy were all provided for. The legislative body ratified the 12 June 1898 Act of Proclamation of Philippine Independence on 29 September 1898.

In April 1898, America declared war against Spain. This was the Spanish-American War. It lasted one hundred and thirteen days. During the conflict, American forces occupied the Philippines. On 14 August 1898, following the surrender of Manila by the Spanish authorities the American Military Government was established with General Wesley Merritt as the first American Military Governor of the Philippines.

Despite the fact that the Americans had established a military government in Manila, Filipino leaders hastened the establishment of a representative republic to strengthen their cause in the eyes of the international community. The revolutionary leaders were convinced that a conflict would soon erupt between the Filipinos and the Americans and inevitably led to the outbreak of hostilities. The Filipino-American War erupted on 4 February 1899.

Had the Philippine Republic been allowed to exist, it could have accomplished its goal of winning its freedom and recognition. If left to its own devices no doubt it could have evolved into a peaceful and orderly government. As early as 1898, this impression was voiced out by an American war correspondent covering the War in the Philippines:

‘There is one point which I think is not generally known to the American people, but which is a very strong factor in the question of Filipino self-government, both now and in any future position. In the West Indies, the greater number of offices and official positions were filled by the Spaniards, either native-born or from the Peninsula.

‘In the Philippines the percentage of available Spaniards for minor positions was vastly less than that shown in the West Indian colonies. The result was that while the more prominent and more profitable offices in the Philippines were filled by Spaniards, many of the minor offices were filled by Filipinos. Therefore, when the Filipino party assumed the government for those districts which the Spaniards evacuated, the Filipinos had a system of government in which the Filipinos held most of the positions, already established for their purposes. It was but necessary to change its head and its name.

‘This fact simplified matters for the Filipinos and gave them the ground upon which they make their assertion of maintaining a successful administration in those provinces which they occupied.’

Tweet

My ‘Tall Dark, and Handsome’ younger brother, Hermes

My ‘Tall Dark, and Handsome’ younger brother, Hermes

Renato Perdon

In commemoration of the 70th birth anniversary of my TDH younger brother on 28 August 2016, I am posting this piece....

Looking back at the Spratly Islands issue

Looking back at the Spratly Islands issue

Renato Perdon

The forthcoming decision of the international tribunal concerning the case filed by the Philippines questioning China’s ‘nine-dash’ line claim based...

The Largest Memorial to Jose Rizal in the world

The Largest Memorial to Jose Rizal in the world

Renato Perdon

(In commemoration of the 155th birth anniversary of Jose Rizal we are posting this short piece to remind Filipinos all over...

RELOAD YOUR DREAMS - Rebecca Bustamante Inspires Toronto

RELOAD YOUR DREAMS - Rebecca Bustamante Inspires Toronto

Michelle Chermaine Ramos

On Friday, August 19 2016 iKUBO Media in cooperation with Chalre Associates hosted Reload Your Dreams at the YWCA at 87 Elm Street in downtown Toronto....

My ‘Tall Dark, and Handsome’ younger brother, Hermes

My ‘Tall Dark, and Handsome’ younger brother, Hermes

Renato Perdon

In commemoration of the 70th birth anniversary of my TDH younger brother on 28 August 2016, I am posting this piece....

HWPL to Host “2nd Annual Commemoration of the WARP Summit” in Seoul, South Korea in September

HWPL to Host “2nd Annual Commemoration of the WARP Summit” in Seoul, South Korea in September

Marilie Bomediano

Heavenly Culture, World Peace, Restoration of Light (HWPL, Chairman Man Hee Lee) is hosting its “2nd Annual Commemoration of September...

Ambassador Gatan Celebrates Summer Reunion with PAG Artists

Ambassador Gatan Celebrates Summer Reunion with PAG Artists

Michelle Chermaine Ramos

The Philippine Artists Group of Canada celebrated their annual summer reunion with Ambassador Gatan, Mrs. Debbie Gatan and Consul General...

LUNIJO’S MISS GRAND CONTINENTAL QUEEN CANADA PAGEANT A CLASS OF ITS OWN

LUNIJO’S MISS GRAND CONTINENTAL QUEEN CANADA PAGEANT A CLASS OF ITS OWN

Li Eron

This year's Taste of Manila in Bathurst Street disrupted traffic in a good way for it being one of North...

Durham Crossover Basketball team wins tourney

Durham Crossover Basketball team wins tourney

Dindo Orbeso

Durham Crossover Basketball team won the U11/U12 Last One Standing Tournament held last August. 20-21, 2016 at Bill Crothers Secondary...

- Summer Super Liga 2016 Volleyball Fiesta sa Riyadh matagumpay na nagbukas

- APCO-led ASCON receives $48,954.00 ClubGrant

- Auburn launches Sydney Cherry Blossom Festival

- Phil-Aus leaders for better services in Cumberland

- BANC’s BAYANIHAN SPIRIT IN FULL FORCE

- Winter Escapade 4 Launched in Toronto

- A Star–Studded Cast leads the 13th Visayan Association Anniversary and Miss Visayas Australia Coronation Night

- Maria Cecilia Caballero Zabala-Pedir - “Cez Zabala” Visual Artist

- FLERRIE V, THE VISUAL ARTIST

- LONDON TO HOST WORLD PREMIERE OF NEW MUSICAL MARCO POLO – AN UNTOLD LOVE STORY

- White Camel Youth Basketball Camp inilunsad sa Riyadh

- Knights of Columbus # 9144 Pilgrimage to Quebec

- Fil-Can Basketball’s Matthew Daves Gets US Scholarship

- Bus Tour - Eastern Canada, PEI & the Maritimes

- PIDCs MABUHAY PHILIPPINES FESTIVAL SET ON SEPTEMBER 3 - 4, 2016

- Celebrity chef Segismundo presents Flavours of the Philippines in Sydney

- Acers Virgin Mobile wagi sa SAMARITAN season 4 sa Riyadh

- CANADIAN SEN. ENVERGA WITH FRIENDS

- Members of Canada's multicultural communities rally for change

`CON AMOR’ FOUNDATION B0ARD MEMBERS VISIT PROJECTS IN PHILIPPINES

`CON AMOR’ FOUNDATION B0ARD MEMBERS VISIT PROJECTS IN PHILIPPINES

By: Orquidia. Valenzuela, as reported by Myrla Danao

Businessman Jaap van Dijke, chairman and two board members, Myrla Danao and Dr. John Deen of Con Amor foundation in...

Art Creations

Art Creations

Vicente Collado Jr.

Welcome!

Many believe formal training is a prerequisite to quality in painting. Not a few will agree with me one can...

THE CHILDREN IN DON MANUEL GK VILLAGE

THE CHILDREN IN DON MANUEL GK VILLAGE

Orquidia Valenzuela Flores

Sixty-three children from age three to six years, in the very poor community of Don Manuel village in Barangay...

Contents posted in this site, muntingnayon.com, are the sole responsibility of the writers and do not reflect the editorial position of or the writers' affiliation with this website, the website owner, the webmaster and Munting Nayon News Magazine.

This site, muntingnayon.com, the website owner, the webmaster and Munting Nayon News Magazine do not knowingly publish false information and may not be held liable for any direct, indirect, incidental, consequential or punitive damages arising for any reason whatsoever from this website or from any web link used in this site.